The World Bank believes that urbanization will be “the single most important transformation that the African continent will undergo this century”, with over half of the population set to live in cities by 2040. This will manifest as 40,000 people moving to cities every day for the next 20 years. While much of the architectural discourse around Africa's future focuses on cities, rural areas are often ignored. This has however been the preoccupation of Italian architect Valentino Gareri, founder of Valentino Gareri Architectural Atelier and Senior Designer at Bjarke Ingels Group.

With 60% of children between 15 and 17 in Sub-Saharan Africa currently not attending school, Gareri has proposed a new architectural approach to school design, founded on pillars of adaptability, modularity, and sustainability. In this interview, Gareri speaks with ArchDaily's Niall Patrick Walsh on the origins, concept, design, and future of his school prototype, as well as his own background in architecture.

ArchDaily (Niall Patrick Walsh): Could you give us an insight into your background in architecture?

Valentino Gareri: I completed my studies at IUAV - University of Architecture of Venice, specializing my interests in sustainable design. Professionally speaking, my path as an architect has been strongly influenced by my work experience in practices like Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Mario Cucinella Architects, and BIG where I work at the moment as Senior Designer in the New York office.

In 2019 I decided to found Valentino Gareri Architectural Atelier, my ‘locus amoenus’ where I develop and do research on topics and areas I am strongly passionate about.

AD: What inspired you to become involved in designing these prototype schools for Africa?

VG: I was sadly impressed by reading that 60% of children in sub-Saharan Africa between 15-17 don’t go to school. And one of the reasons is the lack of educational buildings. What happens is that children have to walk for miles to the closest school, and often they end up quitting. I wondered what I could do, as an architect, to help and improve this situation.

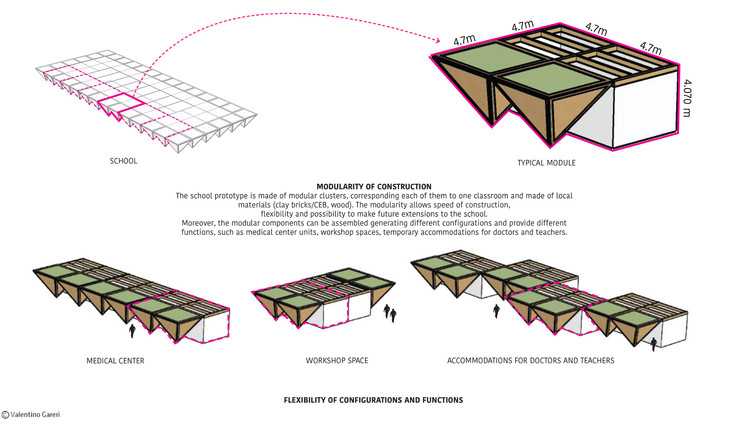

The prototype modular school comes from the awareness that modular design can drastically reduce the costs of construction, facilitate and speed up the building process, and hopefully contribute to helping the diffusion of educational buildings in those areas.

AD: What was the driving concept behind the school design? In particular, what inspired the sculptural triangular geometry?

VG: The driving concept comes from far away, I guess from the purpose that drives me as a human being first, and then as an architect. I believe that art, in general, has the duty to inspire people to hope for a better world. Among all the forms of art, architecture is the discipline that, more of the others, has the power to shape our world and our future. The primary role of architects is to respond and give solutions to specific needs through the shape and geometry of their design. In the case of the prototype modular school for Africa, the module is the result of the combination between a local need (in this case the rainwater collection) and the vernacular architecture and local art. A common element of everyday life (in this case the water tank) is turned into Architecture. I call it ‘UTOP-TICAL ARCHITECTURE’, an architecture where the utopia and the practical are combined together.

AD: Processes and adaptability is an important aspect of the design, both adaptability of function, and adaptability of form. Is this a common feature of your architectural outlook?

VG: I think that the future of architecture will be affected by two needs: the idea of providing large flexibility of functions, and the need for reduction of cost of constructions. Combining the two aspects can become very effective, especially in a context like Africa. In this prototype, the same modular component can be used for different functions, such as medical units, temporary accommodations for doctors and teachers, or units for a workshop.

I believe that diffusion on a large scale of modular design in the future can drastically reduce the costs of construction: repetitive and pre-fabricated components, easy to produce and mount, combined together to create something extraordinary. And the opposite of what someone thinks, there is no risk that this will create buildings that look all the same. Since every building has to deal with different constraints and provide an answer to the specific context where it sits on, the combination of these modules will always differ, as will the final outcome.

AD: The prototype contains an impressive specification of sustainable features, such as water tanks, vegetated planters, and local materials and construction techniques. Was it a challenge to engage with local techniques and processes as someone not based in Africa?

VG: At the beginning of a new design, a large amount of time is dedicated to the study of the context we are dealing with, the local environment, materials, and techniques of constructions and history. The more knowledge we get, the easier we will find the best answer to that specific site and brief. The initial apparent challenge becomes excitement and motivation to find the key that makes everything work together, like a puzzle's missing piece.

In this school the sustainable design is not provided by simply putting solar panels on the roof: it’s an integral part of the whole vision. Sustainable devices are pushed such as a way to inform and shape the geometry of the building. Each triangular element contains a water tank of 1m3 for the rainwater collection, and on top of it sits a planter box where vegetation can grow from and spread out through wire trellis, providing a low cost and sustainable additional shading layer to the school. Moreover, the vegetation grows and spills out into the internal courtyard, introducing the component of nature in the educational experience.

However, I believe that it is not enough discussing sustainability anymore, we should rather start talking about the ability to sustain and support the fragile relationship between ecosystems, humans and mother nature. Not only by designing energy-efficient buildings, but rather by adding improvements to the built world, both at environmental and social levels. In this sense, this prototype is not just a design of a school, but rather a model of thinking that can be replicated in different areas.

AD: To what extent was your prototype informed by your view of education and schooling?

VG: Educational buildings are extremely important in the way children experience their first years of life. The educational process starts from the buildings themselves first, and from the books later. That’s why architects have a big responsibility: with their design they can inform in a good, or a bad way, the society of the future. One important aspect is flexibility: the school is not just a school but rather a machine that should be designed such as a way to be used by the whole community, and every time of the day. In this school, each classroom itself is extremely flexible and can host a wide range of didactic activities.

The second aspect is the relationship with nature: in this project, the triangular shape is the result of sustainable devices and draws inspiration from the vernacular architecture and art patterns, but the triangle is also the best shape which both provides solar shading still allowing the daylight to come into the classrooms. This series of triangular elements creates a monumental colonnade experience that allows avoiding any additional shading devices, which would affect the outdoor view from the classrooms. The internal courtyard allows different educational activities, providing a protected space where all the classrooms face towards to.

The constant perception of nature is extremely important, and maybe because I vividly remember my primary school where blinds were down for the most part of the day. That poor design created a memory in me which is still vivid, after 30 years.

AD: There is a lot of interest in the development of the African continent, and the empowerment of rural areas through infrastructure and education. Do you think we will continue to see an architectural typology such as yours evolve to meet this demand?

VG: I really believe that the best way rich countries can help poor ones is not by donating food or money, but by facilitating the diffusion of education. Of course, there are other complex aspects to take into account, but this would be a great first step. In addition, as architects, we have to make sure that the development of these areas is not seen as something imposed by the local population, but rather something that grows from their ground and speaks the language of their traditions and culture.

Let’s build schools, and universities that will produce other architects who will keep doing so, and doctors who will look after them, and engineers who know how to use wisely their country's resources; and possibly an adequate political class able to transform their dreams into reality.

AD: Are there any final reflections you have on how this project sits within your broader architectural outlook?

VG: This project is the result of my tentative mission, with the tools of an architect, to provide an answer to a problem. And I spent energies on this prototype because I believe that, as architects, we have a big responsibility. Not only a responsibility towards the environment. We also have ethics and social responsibilities. Why shouldn’t children in Africa dream to have a school, and a nice school, like all the other kids in the world?

And extending the thought to a wider context, in a society where, for the first time, new generations are starting to doubt that their future will be better of their parents' one, architecture should inspire people to dream. That’s why I like to think that ‘DREAMING IS MORE’.

Society is changing, and much faster than the past. ‘Dreaming is more’ is not an unrespectful reaction to the masters of the past, but rather an awareness that architecture can’t speak (anymore) to the new generations with a language of three generations ago. And as we said before, ’dreaming is more’ doesn’t mean designing un-feasible and expensive buildings. Good architecture is price-less, not price-full. Architects should be driven by the desire of creating out-of-ordinary buildings, but at the same time being cost and environmentally respectful. We have seen how modular design can be very efficient in this sense.

Architects have the responsibility to give a big contribution to make our planet a better place where we can live in today, and the best home for the new generations tomorrow.